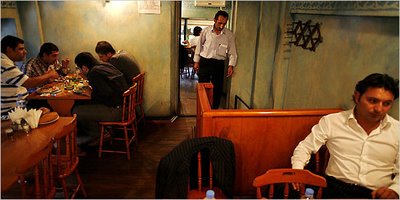

Tarihi Karakoy Balikcisi is small, but regarded as one of the best fish restaurants in Istanbul.

Photo: Yoray Liberman for The New York Times

Video

Choice Tables

Istanbul: Fresh as the Morning, or Rooted in Centuries Past By HENRY SHUKMAN

Published: October 15, 2006

NAPOLEON said that if the world were a single state then its capital would be Constantinople. Even today, amid the traffic-choked streets of modern Istanbul, among the high-rises, the steep alleys and the glowing ancient churches and mosques, you can still feel exactly what he meant.

The air is thick with centuries of civilization, hallowed by history. Above the Golden Horn, once the wealthiest stretch of water on earth, hovers Hagia Sofia, perhaps the most beautiful church on earth, built in A.D. 537 by the Byzantine emperor Justinian with a dome so broad it was not superseded for a thousand years, until St. Peter’s in Rome. Just a quarter-mile away floats its rival, the Blue Mosque, finished in 1616, after the city had fallen to the Muslim Turks. Islam and Christendom; East and West; Asia and Europe: the clichés are true, they do all meet here, and have brewed up an atmosphere unmatched on the planet.

As you’d expect in the capital of the world, there are restaurants from all over. But I didn’t come to Turkey to eat Chinese, Italian or Russian. Cognoscenti say that Turkish is the best of the eastern Mediterranean cuisines, so I sallied forth in search of the most interesting indigenous kitchens.

As a visitor to Istanbul, you’re sure to be sent to Kumkapi, a district packed with fish restaurants. In fact, it’s nothing but fish restaurants, and by night it’s busy, frantic, overwhelming — a bit like wandering into a cross between a hotel theme-night party and a 70’s disco. Bright lamps, waterfalls of fairy lights, zithers and tambourines raging up and down the little pedestrian streets, amid terrace after terrace of outdoor tables — it gives new meaning to the word garish. Vendors stroll around selling everything you might need: Cohibas, dolls, teddy bears, and I even saw one man with a giant tin sailing ship hoisted on his shoulder.

With the Bosphorus, the Sea of Marmara, the Black Sea and the Aegean all within a morning’s drive, Istanbul is a great city for fish. But more interesting than any place in Kumkapi is Tarihi Karakoy Balikcisi in the Karakoy district.

Finding the restaurant, however, just behind the fish market near the Galata Bridge, is anything but simple. Down an alley lined with hardware stalls, past 200 yards of screws, drills and hinges, all that gives it away is a wood-framed doorway and a little display window with a small sample of the day’s catch. Everything here is of the day. When they run out they close. And it’s lunch-only, consisting of two tiny upstairs rooms and an even tinier one downstairs. You can’t make a reservation, although you can reserve a particular fish if it’s in (“Hold the sole, we’re on our way”). Choices go up on a blackboard.

Its owner, Hakan Ozkaraman, owner also of a ball-bearing store round the corner, is passionate about fish. “I’m amateur — this is the special thing,” he said, raising a finger. “Here, just I am selling fish. Not ambience, not view, not fancy plates — just fish.”

Start with the locally renowned fish soup, a rich chowder with flat-leaf parsley that will allay any immediate pangs of hunger. While our next courses were being prepared we had a plate of raw vegetables and herbs — baby romaine, rocket, carrot, cucumber, sage and mint, all coated in a thin lemon dressing.

Mr. Ozkaraman has identified a particular bay near the Dardanelles (whose location he prefers not to reveal further) where the currents keep the water the cleanest in the eastern Mediterranean, he said. Only small fishing craft work there, and all his fish comes from it. But he was emphatic about the sources of everything on the table: the vinegar from a farm in the hills is so natural it has to be thrown away if not finished within a few weeks. Likewise his olive oil comes from a particular Anatolian farm.

We followed with a kebab of rolled fillets of sole brushed with olive oil — clean and exquisite. A specialty is the sea bass wrapped in parchment, which arrived like a parcel on the table. Inside it, along with the sea bass fillets, were roasted tomato slices with blackened skins that added a richness that one was sternly instructed to mop up with bread at the end. This is the kind of hole in the wall one dreams of finding. No wonder it has been going, though a succession of owners, since 1934.

From the modest to the opulent: Asitane, a white-cloth establishment with a terrace under the almond trees at the back of the Kariye Hotel, offers not just rare Ottoman cuisine, but actual dishes from a feast given in 1539 by Suleiman the Magnificent to celebrate the circumcision of his two sons (which may not sound too appetizing, but the dishes are sumptuous enough for an emperor).

Under the Ottoman Empire the guilds of cooks were fiercely secretive about their culinary tricks. Consequently few recipes survive from the four and a half centuries of Ottoman rule (1453 to 1918). In a district of old houses just off a little square lined with plane trees, next door to one of the finest Byzantine churches, St. Savior in Chora, Asitane has devoted itself to the re-creation of this lost cuisine. Eating here is a live history class.

I began with chilled tamarind juice in a misty glass — sweet with the tang of tamarind, and the color of silt. Then came a mix of starters representing the various colonies of the Ottoman caliphs: Arabic hummus with pine nuts and raisins on a lettuce leaf; tomato with fresh Turkish yogurt; Circassian chicken minced with walnuts; and from Greece, a grape leaf stuffed with rice and sour cherries. Two small dishes in the middle contained olive-and-walnut tapenade, sweet and bitter at once, and a goat cheese so fresh you could catch a whiff of the nanny goat’s hide.

For the main course we had dishes from the actual feast of 1539: ayva dolmasi, melon stuffed with minced lamb, rice, almonds and pistachios, in which chunks of melon added sweetness to the meat; and nisbah, a phyllo basket containing diced lamb and small meatballs stewed in pomegranate syrup. How else to express opulence but by combining? Chicken? Let’s have it with walnuts. Meatballs? We need pomegranates.

This ancient cuisine, though filling, is light in grease and fat, and surprisingly clean. On the other hand, you can see where the pashas got their bellies. Melon wasn’t the only thing stuffed at the table by the end of lunch. The check finally came in a little brass Ottoman casket.

The Turkish-Finnish chef Mehmet Gurs is a star of the moment. With his own TV show and three establishments in his portfolio, he’s something like an Istanbul equivalent of the Naked Chef.

Istanbul has enjoyed a resurgence at the prospect of joining the European Union. Sleek new trams run with great efficiency through the downtown district, Beyoglu, and there’s enough prosperity to support a new level of chic. One restaurant that clearly reflects this is Lokanta, Mr. Gurs’s original retro-minimalist place. You can tell what a chic place it is by the name: “Restaurant.” It also happens to have one of the tallest restaurant lobbies you are likely to encounter (it goes right up to the roof six stories above).

In summer it moves entirely to the rooftop, known as Nu Teras. A light-box of an elevator whisks you up, where the thing that first hits you is the horizon bar — a curving plastic aerie hovering over the rolling city bisected by the Golden Horn. As the sun goes down, the lights begin to stud the gauzy land, and it’s a spectacle as beguiling as the stars overhead. The next thing that hits you is the resident D.J. The music is soft, some kind of Turkish-house-jazz blend, and apparently necessary for the clientele, who are wealthy, youngish and beautiful, and as cosmopolitan as Istanbul. I overheard Turkish, French, German and Arabic. It’s like clubbing for the dining classes, though the food is truly outstanding.

The menu is mostly fusion, but with Turkish notes. We started with shrimp on chili spinach — big, plump, sweet ones set off well by the piquant greens — and a stew of clams with sucuk (Turkish sausage). A nugget of sausage rode on the empty half of each shell, the clam playing off the sucuk’s saltiness with its sweetness — all in an herb broth with toast on the side. Then moans and groans from across the table: the lamb tenderloin had arrived on three small steel skewers, over tabbouleh, a bed of mint and coriander and cracked wheat. My side, the rare north Aegean tuna smothered in a true au poivre sauce worked well: sushi-rare, the fish held its own against the rich, tangy sauce. We finished with a shared hot chocolate soufflé, frothing out of a white espresso cup.

Up on this terrace you could get just a hint of “Lost in Translation” alienation: the airy music, the chic minimalism. It was a bit like a movie — beautiful people, cocktails, the soundtrack, the view, the old mosques glowing like gold crowns among the city’s buildings below. But it seems a friendly measure of civilization to be as concerned with views as Istanbulians are. In summer you can hardly dine except on terraces.

You couldn’t get near Borsa the night we went. Ibrahim Tatlises (Sweet-voice) was performing in the amphitheater across the street and traffic was jammed. We had to make our way on foot the last half-mile to the restaurant’s outdoor terrace. Borsa — which means Stock Exchange — has been going since 1927, and used to be downtown near the Golden Horn and the old stock exchange. Now it has moved to a rather anonymous setting in the ground floor of a conference center. But the food is anything but anonymous. For eight decades this family-run establishment has been renowned for the highest quality Anatolian cuisine.

Anatolia, as one Turk explained to me, is a big word meaning more or less all Turkey that is neither on the sea nor Istanbul. We started with “false” dolmades — not grape but cabbage leaves, stuffed not with meat but rice. These were soon followed by “true” dolmades, with minced lamb, along with a quichelike pie of onion, eggplant and lentils, and some pilchiye — giant beans slow cooked for 10 hours. Light miniloaves of unleavened lavash bread waited in a basket. Then came an ancient Anatolian dish, keshkek, a wonderful mush of wheat and lamb. These were the appetizers: there’s a pleasure in this old Ottoman habit of enjoying several starters communally.

But the high point was unquestionably the sis (or shish) of lamb — cubes close to the size of tennis balls, and tender as the best steak fillet, proving once again as the Middle Ages knew, and the eastern Mediterranean has not forgotten, that there is no better way to cook meat than on a spit over a fire. With a smoky mash of charcoaled eggplant on the side, like the very best food it was both simple and complex, and memorable.

VISITOR INFORMATION

Prices for one without wine or tip:

Tarihi Karakoy Balikcisi, near Tersane Caddesi, Kardesim sok. 30, Karakoy; (90-212) 251-1371. Lunch only; no alcohol; 23 new liras ($15 at 1.53 new liras to the dollar).

Lokanta, Mesrutiyet Caddesi 149/1, Tepebasi; (90-212) 245-6070; 50 new liras. (Lokanta is being renovated and is to reopen on Oct. 25.)

Asitane, Kariye Hotel, Kariye Camii Sokak 18, Edirnekapi; (90-212) 534-8414; 35 new liras.

Borsa, Lutfi Kirdar Kongre Merkezi, Darülbedai Caddesi 6, Harbiye; (90-212) 232-4201; 35 new liras.